It was a milestone that under different circumstances might have led every radio newscast and been plastered across the tops of newspapers from coast to coast. But war was raging and, besides, the nation was indifferent to pro basketball.

At least one major publication, the Chicago Daily Tribune, gave this groundbreaking event a tiny headline and 27 words at the bottom of Page 40. And the article failed to mention why the game was significant.

Admittedly, we have the luxury of reviewing this event through the high-definition lens of hindsight.

This event — the first full-scale racial integration of a major professional sports league — was not achieved by the NFL’s Kenny Washington in 1946 or by Major League Baseball’s Jackie Robinson in 1947, as the history books would lead us to believe. And it did not occur in a heavily populated market such as New York or Chicago.

The first and often overlooked breaking down of the big-league color barrier happened in 1942. It was done en masse, with six players. It occurred without fanfare or police escort.

And would you believe this landmark desegregation unfolded in a small-town bandbox known as the Sheboygan Municipal Auditorium and Armory?

“It’s an untold story that deserves acclaim,” said Bill Himmelman, who would know, as he is considered the authority on pro basketball history.

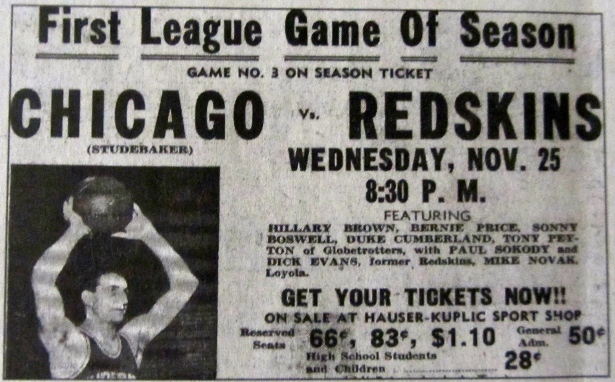

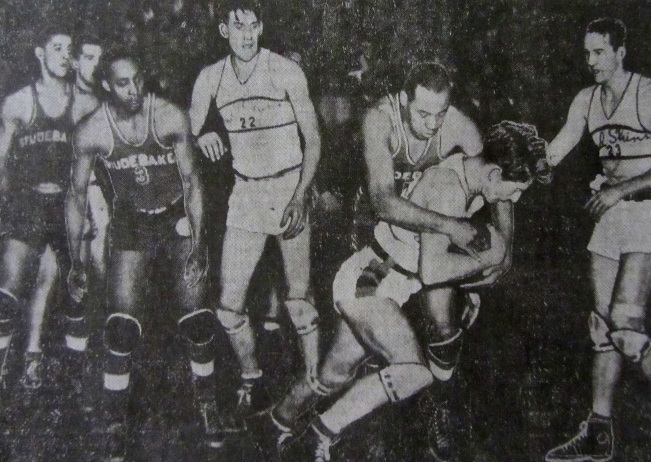

Few of the 3,000 locals in attendance on Nov. 25, 1942, knew the magnitude of the moment when Bernie Price, Hillary Brown, Duke Cumberland, Sonny Boswell, Tony Peyton and Roosie Hudson emerged from their locker room with four white teammates to play the Red Skins. What those fans cared about most was that Sheboygan opened the National Basketball League season on a positive note, 53-45, over the Chicago Studebakers.

Today, historians who recently finished observing Black History Month, and who are following the first months in office of the nation’s first black president, point to that Wednesday night on lower Pennsylvania Avenue as a watershed moment for inclusion.

“There had been token integrations before (in lesser leagues), but this was THE integration that marks the start for pro basketball and for major professional-league sports,” said Himmelman, who served as the NBA’s historian from 1985 to 2002. “About 30 years ago, I had the pleasure of spending time with the Studebaker players. They said they felt shortchanged as the ones who truly integrated pro sports, rather than Jackie Robinson and all the rest. The NBL was the trendsetter there.”

Integration was Sid Goldberg’s brainchild. The owner and coach of the Toledo Jim White Chevrolets broached the idea in an effort to save the league, as conscription had decimated rosters. The NBL’s Chicago entry, sponsored by the United Automobile Workers, piggybacked on the idea and recruited six former Harlem Globetrotter players who were working in the Studebaker defense plant and therefore exempt from the draft. The sprawling plant on Chicago’s South Side made military aircraft engines.

“They were always treated good because they made good money, working at the plant and playing for Studebaker,” said Al Price, whose late brother Bernie was Chicago’s second-leading scorer.

As luck would have it, the Studebakers’ season opener was played in Sheboygan. Some nights later, Toledo suited up four black players — Bill Jones, Shanty Barnett, Al Price and Casey Jones — for their opener. These dual events came eight years before Earl Lloyd was hailed as being the first black player to step onto an NBA court.

“Some of the towns we played in weren’t too cool,” said Price, 92, who still lives in Toledo. “That was just the way people were and how they felt. All across the country, discrimination was going on. Some cities and towns were very prejudiced and others were very receptive. Just like people are today, good and bad. I don’t remember how Sheboygan was.”

The last player remaining from that trailblazing Chicago-Sheboygan game is Red Skins forward Ken Buehler, who scored 14 points against the Studebakers and would be named the NBL’s rookie of the year that season.

“When I played at Milwaukee State Teachers College, we had a black player on the team, so it was nothing new,” said Buehler, 89, who lives in South Palm Beach, Fla. “As for the Studebakers having black players, nobody thought anything of it, as far as race relations go.”

To the city’s credit, the integration experiment appeared to go down without a hitch. The Sheboygan Press reported that “the colored boys looked classy and will undoubtedly do some upsetting before the season ends.”

Perhaps it wasn’t a big deal because for the better part of a decade Sheboygan had played black barnstorming teams and even hosted the Globetrotters’ first training camp, in November 1940.

However, it might be misleading to characterize all-white Sheboygan as an island of tolerance in a nation otherwise divided by Jim Crow-era legislation. For instance, a local announcement for a 1939 game against the all-black Jesse Owens Olympians promoted the Red Skins’ rematch with “these darkies” and used several stereotypes of the era.

Author Robert W. Peterson, in his book “Cages to Jump Shots,” wrote that Toledo found accommodations in Sheboygan only because Red Skins coach Carl Roth had implored Sheboygan Indians baseball manager Joe Hauser, an influential voice in town, to find rooms.

As for the Studebakers, for all we know they may have stayed at a ramshackle hotel near the railroad yard, sleepless and staring at cracked ceilings as an assembly of train whistles and slamming rail cars inhabited the night air.

Two years earlier, the famous Globetrotters, consisting of several of these same Studebaker players, were met with the glare of taciturn hotel managers.

“They were not welcome at the Foeste, which was the nicest hotel in town,” said Frank Zummach, 98, the Red Skins head coach from 1939-42. “They found a hit-and-miss place, the Park Hotel, which wasn’t much of a hotel. Sometimes, and more often than not, they’d go to eat and they wouldn’t (be served).”

So while it may be with pride that Sheboygan embraces its role in big-league sports integration, it must be tempered with the knowledge that the road was filled with potholes and the door was open only a crack. Timing allowed the Studebakers and Jim White Chevrolets to squeeze through, and dumb luck allowed Sheboygan to share in the moment.

(Published in The Sheboygan Press, March 9, 2009, as a staff member of The Des Moines Register)